Taking Technical Cues from the Score: Articulation

3/24/20253 min read

As Neuhaus once said, "Technique is a means to an end." It was his belief, as it is mine, that technique and artistry are two sides of the same coin. Nowhere is this more evident than in the realm of articulation. If we take our cues from the score—not just musically, but technically—we uncover a wealth of physical information embedded in those tiny dots, lines, and slurs. For many composers—Beethoven, Debussy, Prokofiev—articulation is not merely a suggestion. It is a roadmap for how the music should feel in the hands and in the body.

Articulation markings in the score can and should shape our technical approach to the piano. In fact, I would argue that teaching articulation is nearly synonymous with teaching technique. To articulate at the piano is to speak. And like any good speaker, we must learn not only what to say, but how to say it—physically, with clarity, nuance, and intention.

Nikolaev's "School of Piano Playing:" Building Technique from Articulation

One of the clearest examples of this integration between articulation and technique comes from the Russian School of piano playing. In Alexander Nikolaev's indispensible School of Piano Playing (published in the US by Boosey and Hawkes under the title "The Russian School of Piano Playing"), students begin their journey not with legato or scales, but with non-legato, or détaché, touch. They are taught to play simple melodies using only the third finger, releasing the weight of their arm into the key with a flexible wrist.

The flexible wrist serves an essential function: it absorbs the weight of the arm to avoid slamming into the keybed. From the very beginning, the student is guided to create a beautiful tone through coordinated movement, imagination, and active listening. Only later are other fingers introduced, always preserving the non-legato articulation and the arm impulse that supports it.

Staccato comes before legato. It is taught as a quick upward flick of the wrist. Wrist staccato allows for brightness and brevity without sacrificing support from the larger structures. With very young students, I sometimes place a toy frog on their wrist and ask them to make it jump—a trick I learned from the great Irina Gorin. The simplicity of the image conceals the biomechanical precision at work: a textbook example of proximal-to-distal kinetic chain movement, generating energy for a quick attack and release with minimal effort and maximum effect.

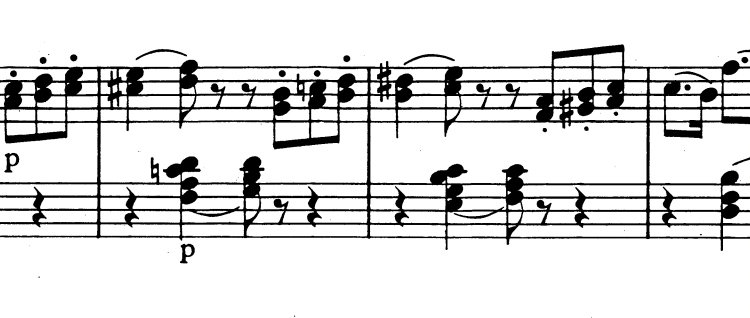

Legato is introduced gradually, starting with two-note slurs. These are taught not only as musical gestures but as physical ones. Students drop into the first note, listen to its decay, and then release the wrist upward to the next. This rolling motion connects the two sounds, both aurally and kinesthetically, creating a single expressive gesture. The progression continues to three-note groups, five-note figures, and eventually scales—each new articulation layered on a foundation of movement.

Articulation as a Technical Roadmap

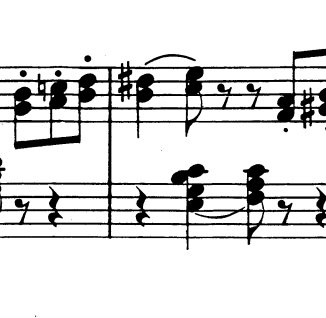

Each articulation implies a movement. Staccato requires a quick release; non-legato a supported detachment; slurs a smooth transfer of weight. When we teach these articulations systematically, we are, in essence, teaching movement—safe, efficient, expressive movement. We are building technique from the ground up, one gesture at a time.

This is why score study matters—not just for musical interpretation, but for technical planning. Every dot, dash, and slur in the score can be read as an instruction for how to move. As I often tell my students: the specificity of your thought determines the specificity of your movement. If you know what you want the sound to do, and you understand what gesture will produce that sound, then your technique will organize itself around that intention.

Too often, we view articulation as an interpretive afterthought. But it is, in fact, one of the most potent tools we have for technical development. And by revisiting the methods we use to teach beginners—particularly those grounded in coordination and articulation—we can rediscover a roadmap not just for our students, but for our own playing as well.